A Riverside Community

Genilson Guajajara is from a quiet riverside community in Maranhão State, Brazil, in the Amazon Rainforest. He is of the Tenetehar, now more commonly known as the Guajajara People. The Rio Pindaré rises in the nearby hills, separating its basin from that of the Tocantins River to the south. The river drifts peacefully by the community. It’s a source of food and transport to the people, and there exists strong spiritual connections for them to the river and the surrounding forest. Culture, spirituality, ritual, and ceremony are very much a part of life here, and a deep interconnectedness pervades the people and landscape.

This is home, where my family and my community live, a setting alive with the sounds of village life, the forest and all its inhabitants in close proximity, whilst the Rio Pindaré gently emanates in the background. It’s from this unique setting that I seek to share my stories with you, giving an insight into the essence of our people.

Genilson Guajajara

Q & A

Describe your community and its people ?

I’m from the Rio Pindaré Indigenous Land, in Serra Preta. It’s located in the northern part of Maranhão. It’s a small territory which used to be 65,002 hectares. Today, it has been reduced to 15,002 hectares, and we are surrounded by farms. There is a highway that cuts through the territory, the BR-316, and other significant developments nearby, like the Carajás Railway and various power lines. It’s a territory that has been heavily invaded.

Our people have had contact for over 400 years. Many were important in the struggle to defend the territory. I’ve always been involved in these struggles. Since I was little, I’ve been participating in meetings, listening to our leaders talk about defending the territory, as well as the fight for other public policies that are important to the community – education and healthcare. I’ve been part of this environment of resistance from an early age, and I’ve always wanted to contribute to the struggle of my people. Photography became a tool for me in this struggle.

In the beginning, it was really challenging for me because I hadn’t had much contact with technology. So the process of learning and mastering those tools was difficult. Though it was also a process that helped me.

I started leaving the territory at the age of 16 to join other movements. During this process, I listened to people from non-Indigenous communities who also supported our fight. I became more curious about our history and how important it is to take care of our territory in a wider context.

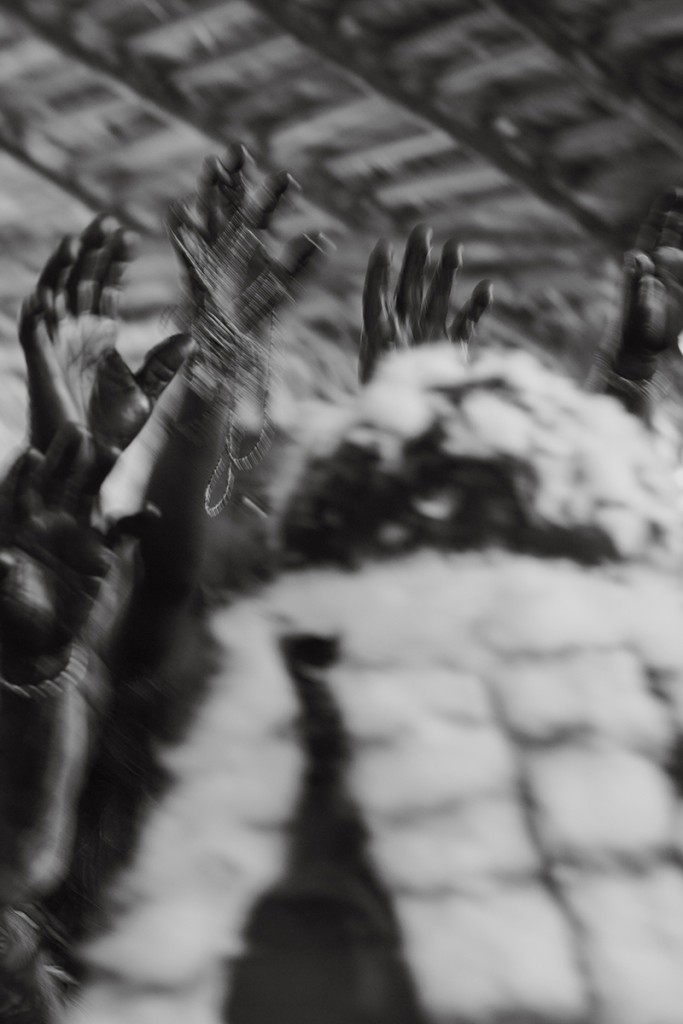

In our community spirituality and interconnectedness is deeply important. Everything has a reason. Everything has a meaning – this can be found in the forest, in the waters and the rains, in our rivers, and in the air.

What does a typical day look like in your community ?

Sustainable fishing and farming is a regular part of our daily lives. The territory has plenty of water and an abundance of fish. We’ll often camp in the nearby fields. In these moments, I always bring my camera, as I like to live and share the experience with others who are working the fields and fishing through the day.

We have a specific time when we prepare the land for planting, connected to the lunar calendar. I learned these ways from our elders. Right now, my family doesn’t always reside in the village as we travel a lot. My partner—one of our community’s leaders travels regularly as do I . We share child care responsibilities, ensuring one of us is always home for our two young children.

Participating in the rituals and the movements that happen in territory are important to us, and we’re always available to support our cacique and community.

I love being with nature, reflecting on everything in my life, and how photography has supported important moments in our territory. We were not truly recognized previously, as our lives were shown through another lens, and we did not have direct participation, this created a very different narrative around our way of life.

Photography was used as a tool that deconstructed our story though a western lens, and could often be prejudiced and lead to another perspective. There are many beautiful things within our territory: the relationships, our daily life, people’s routines, and our rituals. These are really important in my storytelling – our reality.

Are there any struggles that you and your community have faced ? How have you overcome some of these challenges ?

There are many challenges. The first challenge we faced was access to information. Today we live in a period of struggle. We used to fight with bow and arrow, but now our fight is more about ideas. The leaders have always been concerned about us having access to this and other information from the Western world. Though elements of this have helped in fighting for our territory and our protection.

In 1988, the territory was demarcated, though this was also a strategy by the State, as they planned to demarcate only 15,000 hectares.

If we were to analyze how much territory we’ve actually lost, which is now occupied by farms, and cities inside and around our territory,

the area of land would be much greater, areas we know reside in Indigenous Guajajara people’s territory.

Another challenge were the developments that crossed through the territory, like the BR-316 highway. At the time, the community was not consulted and properly informed and we were unaware of the major impact this project would have within our communities. We soon realised the impact. There was more contact with non-Indigenous people in the territory, and accidents often occurred that took the lives of our relatives. We felt more exposed, and realised the significant impacts for our territory.

We also have repeated fires, which are caused by the highway. Subsequently the villages in the community started organizing and considering protection groups, for example we now have a group of women who carry out awareness work, educating others on fire safety and respecting our wider territory.

We have our local Indigenous fire brigade that works to fight fires within the territory through the summer. There’s also the Guardians group, who protect the territory, and its biodiversity.

We’ve been organizing ourselves to think about the future. There are numerous activities that take place within the territory, in spaces like the conversation houses and the school. This has involved a lot of people in discussions as we seek to find solutions that will raise awareness both inside and outside the community.

These activities and discussions are helping us to reduce invasions and to take better care of the land. We have a very large diversity of species within the territory, and this has been thanks to internal organizations involving everyone.

How has your journey as a photographer and more recently a filmmaker supported yourself and the community through these moments ?

Initially it was really difficult as we didn’t have a more focused vision for audiovisual work. My people thought maybe it wouldn’t become as significant, it was hard to envisage a photographer or filmmaker from the territory. Previously, our communities were only photographed by non indigenous people.

Though in 2017, I was creating more photos. I used to photograph daily life in the community and write a little about how I felt. Over time, this work started to circulate in publications.

This was a positive moment, as people from outside now became more aware of how important the role of our organizations were in protection and reforestation. Recently, we had a meeting here in the territory involving all of our organizations. It was organized by the women in the community, I was able to share the materials I had produced over the years. It was an emotional moment. I told them how the work they’re doing has served as inspiration for other territories, other people, and other organizations—and that, in some way, this is having an effect on the society we live in.

Initially, no one in the community truly recognized my work.I was young and starting out. Few people knew me, though my work started to circulate. In 2021, I was nominated for the PIPA Prize—and this had an impact on me and our territory. People started to understand how important this work is to document, this was a hugely positive development.

If Not Us Then Who has been part of your journey as a creative for close to 5 years now, how has their support helped ?

I didn’t have much support starting out. Though things started to evolve, and soon after Joel Redman reached out – Director Of Photography, at Not Us Then Who ( INUTW ). I was curious because no one had ever reached out before, or particularly noticed my work. I went on to follow his work and that of INUTW , the work of other filmmakers and photographers. This inspired and motivated me.

The way that If Not Us Then Who has worked and supported me in my productions has helped me not only as a person, but also professionally.

It has awakened a more critical view of what I’m producing.

The conversations we had during the creative process of the Zine were really important, what I learnt in this space I began incorporating into my own productions, the care of process and taking the time to do things right. It really helped.

The important thing to remember is that before this collaborative work, my work wasn’t well known here in Brazil. Though once my work started reaching new audiences abroad, it seemed like people here started to notice, and that brought a much wider reach. It opened up several great opportunities for me, it gave me access to spaces I never thought I’d be able to reach.

So for me, INUTW is incredible to work with as a collaborator.

You have achieved so much with your work in the last few years. You’ve been part of group exhibitions, you’ve produced editorial work, interned with INUTW and Wildscreen in order to produce and publish your wonderful zine – Ritual, which helped audiences discover more about your community. You’ve also collaborated with the team at INUTW in producing a multi media project at last year’s Freeland Camp in Brasilia which featured your photography prominently and went onto be published worldwide in the magazine Icarus Complex. Describe this journey for you alongside INUTW and some of your highlights ?

I think I would highlight the learning experience, as it was a very dynamic process. In terms of the work we created at the Freeland Camp (Acampamento Terra Livre) – we were at one of the largest Indigenous mobilizations in the world, the camp brings together many different peoples in one place, all fighting for their territorial rights , for respect, and denunciations.

I really enjoy the learning experience, and throughout this project, alongside Joel Redman and Lina Salas, they very much guided me to pay more attention to detail. They helped me produce some really meaningful content.

I enjoy photographing people in spontaneous ways, and I think that’s been something that’s caught the attention of my audience. INUTW’s guidance has supported me in other projects. I’ve been able to create images of people outraged by the mining in their territory, people crying out for help. Being able to share that through photography and bring it into this space is really interesting.

You recently seem to be diversifying into creating more moving image work as well, and participated in “A Day On Earth” the collaborative project that is in the edit stage with INUTW and is to be released later this year. How did you enjoy working on this project, and diversifying further into film ?

I was really surprised when I received the email, and I accepted right away. It was a very important process for me, we had meetings with several filmmakers from different parts of the world. We have a Whatsapp group, and during the filming process, everyone shared their moments of documentation. I got to learn of other people’s communities, it was really valuable.

This has been a very important experience. As I mentioned, many things happen within the territory. When we go out into the field or plan something for a script, the territory always ends up surprising us with something extra.

It was incredible for my community as we learned and saw more of other territories, working alongside them collaboratively.

It’s been such a positive opportunity. I had previously been more dedicated to photography, but I also see the need to produce films and documentaries.

This project connects around 75 Indigenous filmmakers worldwide in a very collaborative format. How important can a collaboration such as this be, for strengthening networks, building bridges between communities and forming new connections ?

On my own, the reach of my work is limited. Though when we start producing something on this scale, the reach of our work expands in a much bigger way. I believe this opportunity is going to have a great impact, allowing more people to get to know my work, the work of other organizations, peoples and their communities.

What has your community’s reaction been to the work you’ve managed to create with them ?

It’s been great. For example, I did an exhibition in my village, my first. It brought together people from all over the territory. It was held at night. We sang during the opening, and afterwards I gave framed photos to the school and organizations.

Today, that school is the largest in our territory, it offers high school education. They hung the photos on the walls and in the hallways, photos of the fire brigade, the rituals, and the women in movement. Afterwards a communications group was created here in the territory, it brought together several young people, and we’ve been able to start some new projects focused on communication, photography, and audiovisual work.

This has further inspired other young people to explore the world of audiovisual and photography. It’s been very important and meaningful for us.

We’ve also been discovering other artists here in the territory—people who do body painting and canvas art. People are being recognized for their creativity, and that’s important. I hope to collaborate with some of them and learn more of their work, so together, we can occupy more spaces.

What projects do you envisage working on in the coming year ?

I’m considering more photography exhibitions here in Brazil. I’ve been invited to participate in some collaborative exhibitions alongside other artists.

Recently, I received an invitation to exhibit together with other Indigenous photographers and artists in a gallery in São Paulo. The opening will take place on the 15th May, and it’s going to be very important for us to present our work there. Brazil has immense Indigenous cultural diversity, though the Guajajara people are still somewhat distant from these spaces.

This opportunity has been really important for us to say: we are here, and that through all the struggles our territory has faced and still faces, we continue to resist. Photography has become a way for us to say that we and our memories are still very much alive.

I also hope to one day exhibit in another country. I would like to bring some of my relatives with me, so we can do this work together. Soon I intend to create further projects. A film and photographs that speak about the Awá Guajás and their rituals. ( a voluntary isolated community in our region )

They’re people who have had relatively recent contact, they have a very strong connection to nature. Their songs are very powerful, and as they chant, they call upon the spirits that care for the natural world. This is something that has been undocumented. For me, it’s very important to one day be able to do something with this community. To support them.

Has your creativity and journey with INUTW helped you to forge better connections in the Indigenous movement, has this been helpful ? Describe what these connections have meant to you ?

Before we started collaborating, there were already numerous photographers and communicators involved with INUTW, though we didn’t really know each other. My work started circulating more once our collaborations were under way. Local organizations here in the state invited me to be part of their projects and collaborate with their institutions. The whole process helped people learn more about my work and understand its importance.

Other organizations that work with Indigenous Peoples have also invited me to participate in different projects. That’s been important because I’ve had the opportunity to meet other communities, and people I had always wanted to reach out to.

It’s been really amazing working with INUTW, they’ve opened up many doors and opportunities for me personally, and for other people to get to know my work, and in some way, to see themselves reflected in my work.

In terms of connecting. I wanted to know a little more of the exchanges that take place between Indigenous communities in Latin America. You were part of a recent trip to Bolivia as part of Povo Indigenas Jachakaranges. Could you tell us more about how this came about and the experience you had ?

For me, this was an incredible experience, it was the first time I had left Brazil. I received an invitation from Justiça nos Trilhos, which is an organization that works with communities affected by mining.

I participated in a two-year political education program with them. As part of this training, we undertook communication work, that’s when I first got into this field of work. We worked on photography, and this led to us producing content within the territory.

We created a newsletter and a collective page called Pinga Pinga. It brought together several young people from communities impacted by mining. Each month, we published a newsletter. People from the communities would write about their experiences and send them into the editorial team, creating an online newspaper.

Sometimes it included reports or complaints. Once, a person from a community was run over by a train and died. Someone reported it, but the legal team implied the person was drunk. So the team made a satirical cartoon, showing an armadillo with a bottle of cachaça, getting run over on the tracks. The cartoon read, “Run over by Vale’s train, though the lawyer accuses him of drunkenness.”

We had to do that kind of thing because the company never wanted to take responsibility . The content started to circulate, and we began distributing the pamphlets in the territory. We also included things like recipes, how to make a traditional sauce and wrote out the ingredients. We used cartoons, poems, and things like that. It was really interesting.

We then did a workshop around small-scale media productions using cell phones. At first, we created everything using our phones and free editing apps, both for videos and photos. At Justiça nos Trilhos, there are people from journalism backgrounds and photographers who have always led workshops with us.

The trip to Bolivia happened because we had known each other for a long time. I had already worked with Justiça on some news articles and communications projects. So they invited me and asked if I wanted to take part in an exchange program in Bolivia. I said yes. We spent 15 days there, learning about the culture.

It was really meaningful for me because it was a different language and a whole other world. I wasn’t used to the cold, but I loved the opportunity. We visited many communities, and what stood out to me was how freely they live. Unlike in Brazil, where landowners fence off their land, I didn’t see that.

Another moment that stood out was when we went to Salar de Uyuni, and I had the opportunity to photograph the local people. It was an incredible moment.

We visited other cities, and went to the Amazon side of Bolivia, to a place called Rurrenabaque.

A stunning place, surrounded by nature. Though the impact of gold mining was very present. There’s a river surrounded by mountains of stone, polluted due to gold extraction. That deeply affected me, as around the river are communities that depend on fishing and hunting. The river was contaminated, and it was clearly having a large impact on people’s lives, especially children.

I created some images in this community, a community very vulnerable to these mining activities. Somehow the people were happy though, the kids were playing, and that really stayed with me. It made me reflect on our own land, how these development projects harm us, physically and spiritually.

So yes, this experience marked me deeply.

Do you have a message for up and coming Indigenous storytellers who are at the beginning of their journey ?

I would say that we have to throw ourselves into our work—body and soul—always. That we have to feel what the other is feeling, to know that we belong to place, even if just for a moment, to say: “I am from here, I will return.” And when I’m no longer here, what I’ve done will still remain alive, in the memory. And I say memory because photography endures.

I think it’s also about working with deep respect, respecting the other’s place. If someone invites us to eat fish or roasted meat, then let’s eat and enjoy that moment, because it’s unique. Let’s jump in the river with everyone else and feel the cold water. Let’s wake up at five in the morning and listen to the birds calling us to watch the sunrise. Let’s smell the leaves, the water. Let’s feel the pure wind on our faces, sit on a tree trunk, and reflect on a photographic narrative: What story do I want to tell?

That’s essential for our growth, as photographers, as Indigenous People.

Any final thoughts or words you want to share ?

My gaze is like an arrow that pierces the flesh and touches the spirit.

The purpose of my photography is to move people—to make them feel that place, even if just for an instant.

This in itself, is enough to change an entire perspective about ourselves – Indigenous Peoples.

Genilson Guajajara

Genilson’s work and nature centric stories from other wonderful Indigenous creatives are regularly shared though our social media channels. Follow us in these spaces to find out more.