Water is life. Yet our freshwater (which only makes up 2% of the world’s water) is under increasing threat from rapid climate change, contamination disasters and population growth. The future of that 2% is in jeopardy. Climate change is making wetter regions wetter, with heavier rainfall causing flooding and faster movement of water into the oceans, while dry regions are getting drier, causing drought. Inland glaciers melting is also reducing our freshwater stocks. Meanwhile global demand is set to increase by a third by 2050, according to the UN.

But we already have the solutions.

‘Nature-Based Solutions‘

The theme of World Water Day 2018 is ‘Nature for Water’ – using the wisdom of natural ecosystems to tackle problems such as floods, droughts and water pollution. It calls for ‘Nature-Based Solutions‘ such as restoring wetlands and forests to prevent flooding, rather than simply building concrete flood defences, or harnessing natural wetlands for groundwater recharging and water storage rather than just building dams – prioritising ‘green infrastructure’ in water management planning, rather than just ‘grey infrastructure’.

Forests and wetland ecosystems are crucial for water security

Forests have a high capacity to retain water in the soil through their roots and help to maintain the water cycle by transpiring through their leaves, while wetlands improve water quality by filtering out pollutants. However at least 65% of forested land is in a degraded state and an estimated 64-71% of natural wetlands have been lost since 1900 as a result of human activity (UN World Water Development Report 2018).

Indigenous peoples and local communities care for an estimated 22% of the Earth’s surface, and protect nearly 80% of the remaining biodiversity on the planet, while representing only close to 5% of the world’s population (ILO, 2017), as stated in the UN report on nature-based solutions released this week. The more that nature-based solutions take central roles in water management planning, the more likely they are to work in harmony with local indigenous peoples and their ancestral knowledge. Indigenous communities have been operating ‘nature-based solutions’ for millennia, developing intimate understanding of the water sources and ecosystems in their territories by actively engaging with it both physically and spiritually.

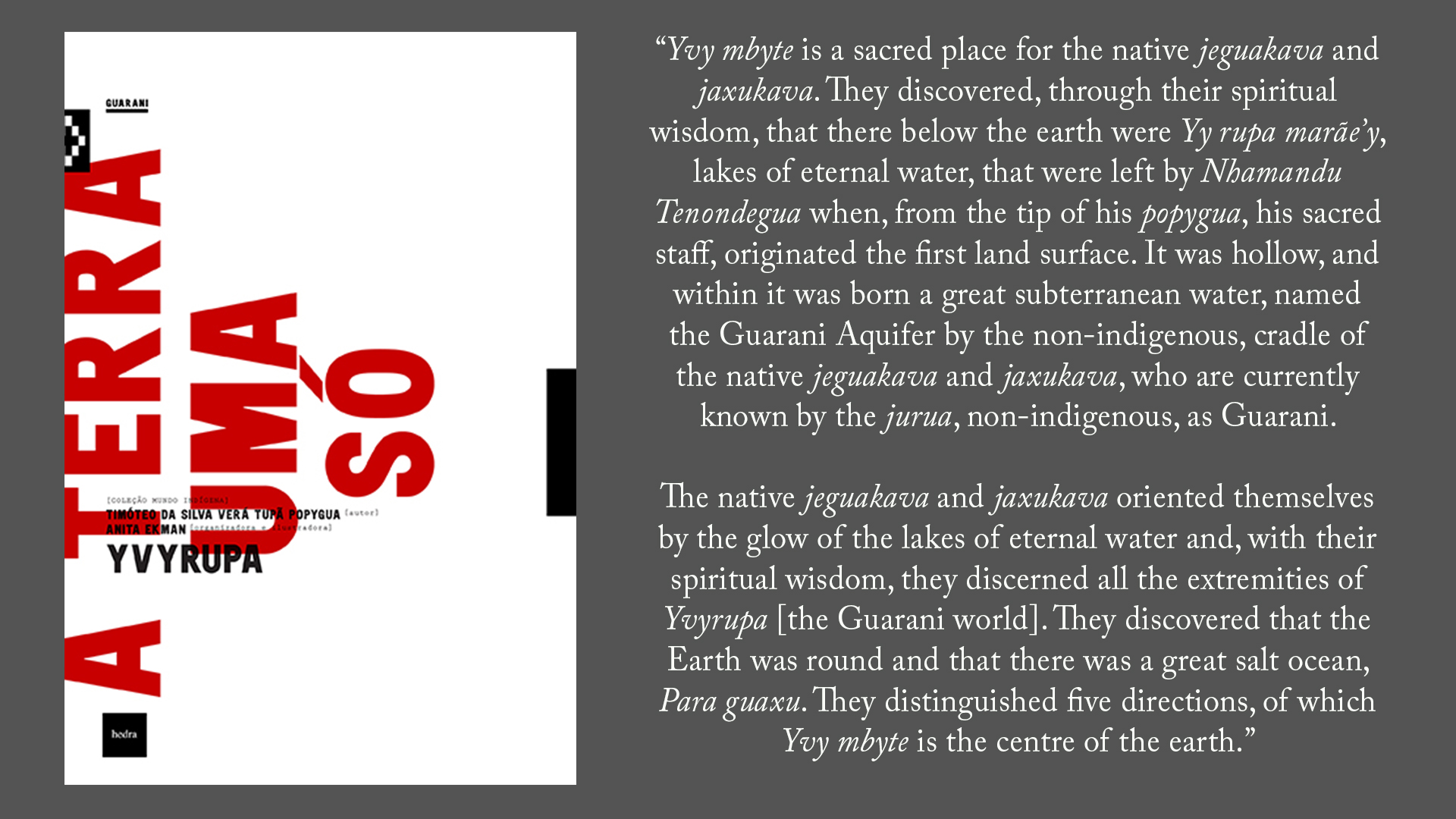

One of the largest sources of fresh groundwater in the world is the Guarani Aquifer, covering 1.2 million sq km across Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay. It is named after the Guarani people and is sacred to them. Guarani author Timoteo Popygua writes about its meaning for his people in his new book ‘Just One Earth’.

Timoteo warns against the threats to their precious water source, saying, “This water was left by our creator; water is sacred for the Mbya Guarani peoples, the origin of all human beings, it cannot be destroyed by capitalism. We live in the great garden of our creator, we must care for human life.”

From privatisation of water sources and restricted local access, to mass contamination disasters from mining and river stagnation from dam constructions, indigenous peoples across Brazil and the world are facing assaults on their water.

When the Fundão tailing dam in Minas Gerais, Brazil, ruptured in November 2015, it unleashed 50 million tons of toxic waste from one of the world’s largest iron mines into the Doce river. It was the largest environmental disaster in Brazil’s history. The Mariana Disaster, as it is known, killed nineteen people and completely contaminated more than 500km of the Doce River.

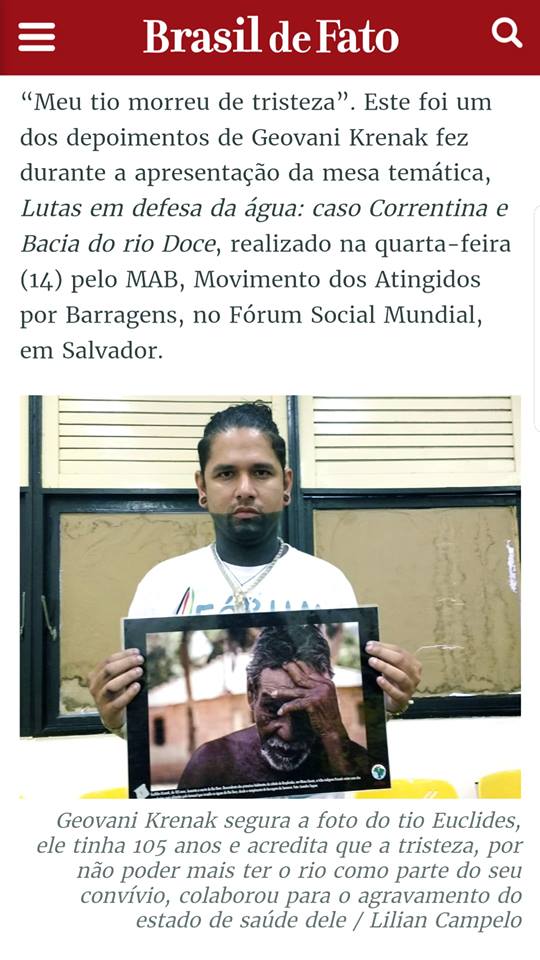

The Krenak people who live along the Doce River have had many aspects of their way of life destroyed, the river being central for fishing, bathing and many traditional ceremonies. They have been denouncing this crime of gross negligence and seeking justice, such as at the UN Climate Conference COP23 in Bonn, as is shown in this video of regional leader Geovani Krenak.

Geovani Krenak has been speaking again this week at the Alternative World Water Forum in Brasilia, the people’s counterpart to the ‘Forum of Corporations’, the 8th World Water Forum, also in Brasilia. He stated:

“My people understands that we are the river, we are the water, and this makes us closer to the essence of Mother Earth. When people begin to distance themselves from this feeling, that’s when the destruction, the devastation and the privatisation of water begin to happen. They forget that they too are part of nature, they are part of Mother Earth.”

This is at the core of how indigenous peoples have developed great resilience; understanding themselves as within nature, they interact with it in tune with its own rhythms, yet also proactively to ‘optimise’ their environment in ways that help nature’s own ‘engineering’ function at its best, and benefit their communities. Just as ‘nature-based solutions’ do.

“My uncle died of sadness” – Geovani Krenak at the the Alternative World Water Forum

The UN report recognises the role for indigenous knowledge: “….community-driven water projects can foster a more diverse and locally adapted set of solutions to water and natural resources management.”

However there is a long way to go to have really inclusive infrastructure planning in place, that involve indigenous communities in mutually acceptable ways. The report warns, “to adequately benefit from contributions of indigenous and tribal peoples…it is imperative that their socio-economic and environmental vulnerabilities are addressed, and their rights are respected.”

Time and again huge infrastructure projects are planned with absolutely no consultation of local communities, no collaborative planning, no process for free, prior, informed consent, which is required by several international treaties, and a very limited share of the benefits generated, if any. The Standing Rock Sioux drew worldwide attention to the ongoing dismissal of indigenous demands in such constructions.

With increased interest in nature-based solutions, there is hope that governments can stop viewing indigenous communities as obstacles to drive over, and start to really value their extensive reserves of knowledge, with all the keys that they hold to some of our most urgent rising problems.

Jaye Renold